Use the information you have gathered about student

progress from the assessments in this unit to guide your

approach to this lesson. As students are creating and

illustrating their “What if” stories, circulate and ask

questions, especially of students still struggling with the

multiplication and division concepts. As appropriate, ask

questions such as:

- How does your number sentence describe your story?

- What does each number mean?

- Can you point to the part of your drawing (or physical model) that your numbers refer to?

- What are your equal groups?

- What number tells how many are in each group?

- What number tells how many groups you have?

- Do you have leftovers?

- What should the people in your story do with the leftovers?

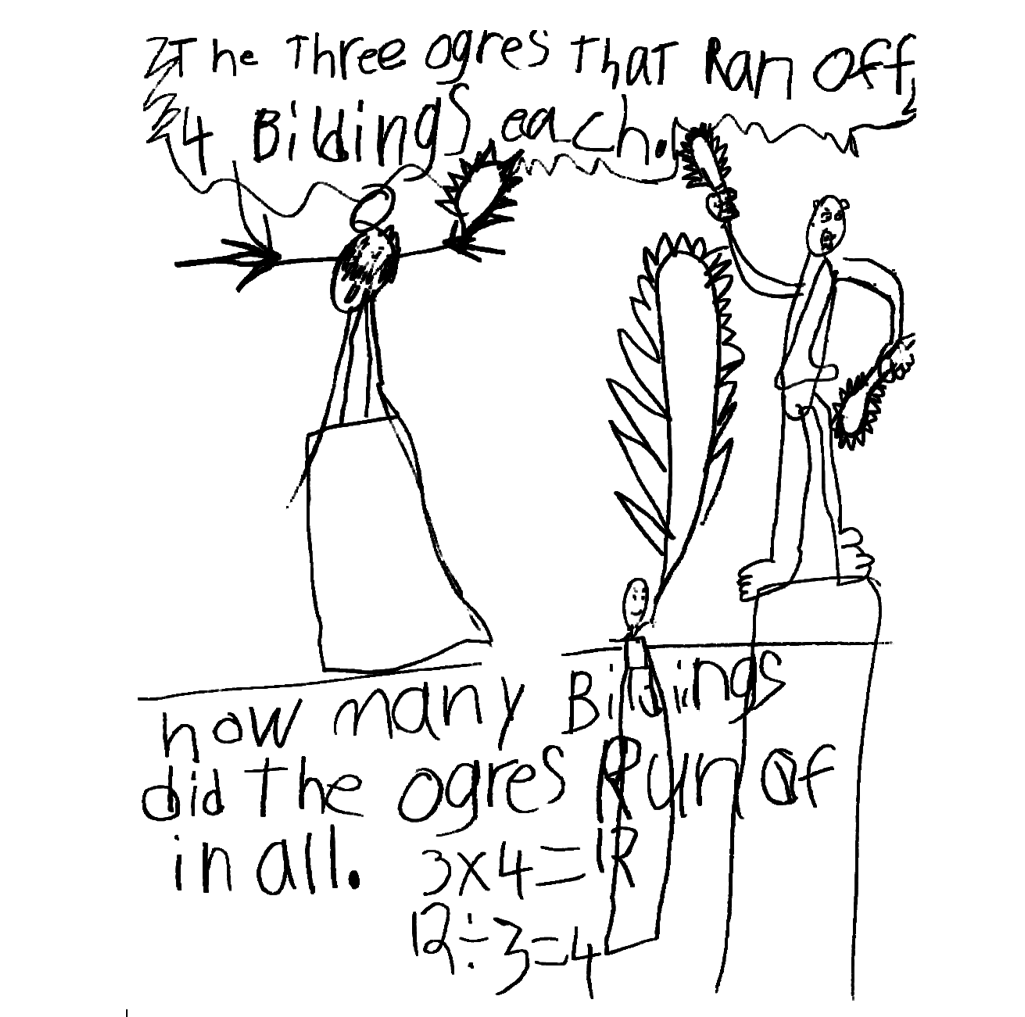

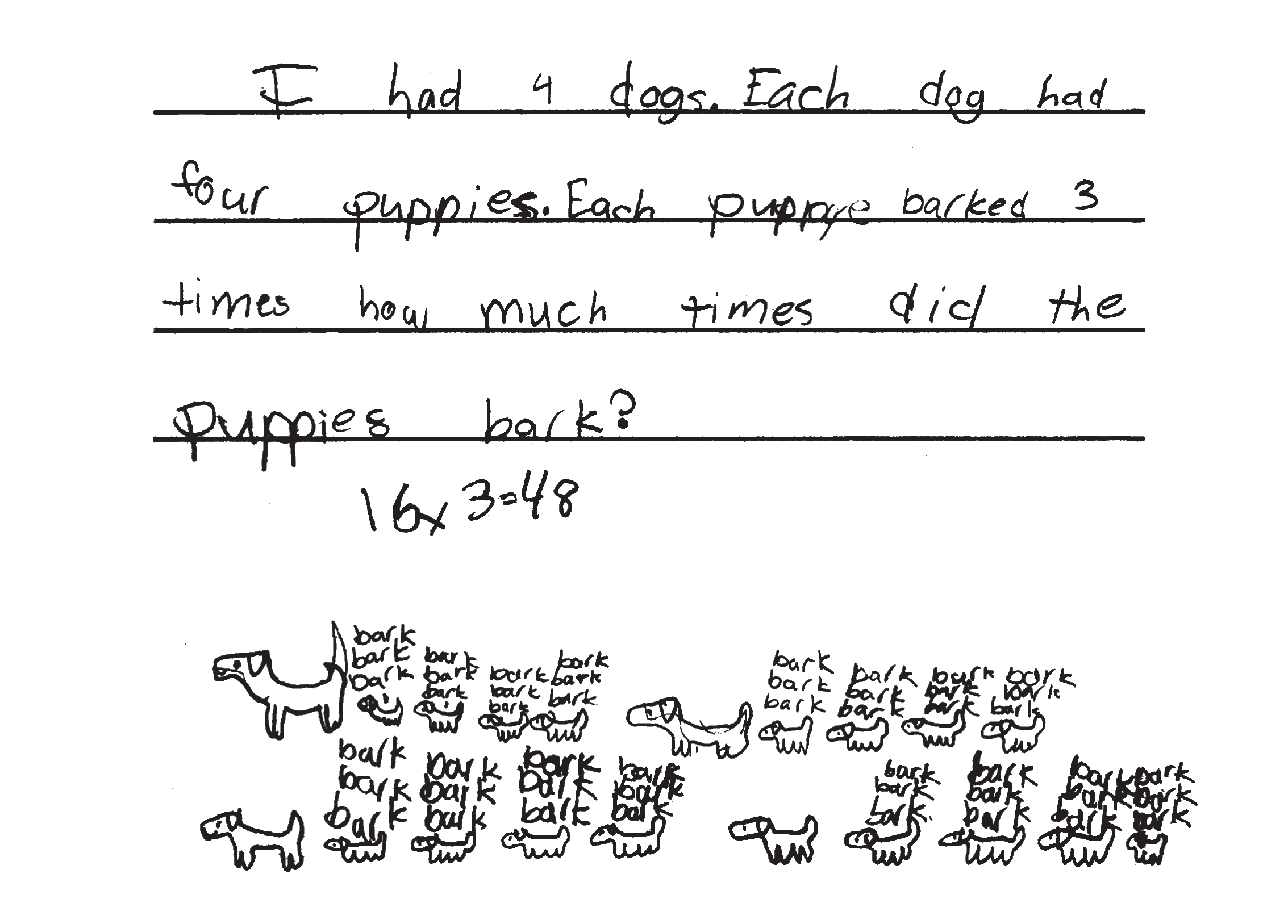

Ask students who are comfortable with the concepts to write

two number sentences for each picture. Some students may

recognize the inverse relationship between multiplication and

division and that their stories may be appropriately described

by either or both sentences. See the student story in

Figure 1.

Introduce “What if” Problems.

Tell students the

summary of a familiar fairy tale or folk tale with

numbers in the story. One of the characteristics of

fairy tales is that events, objects, or characters often

appear or happen in threes, sixes, or sevens. Some

examples of fairy tales or folk tales with recurring

numbers are:

- The Three Little Pigs

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

- Rumpelstiltskin

- Six Foolish Fishermen

Add new characters or plot details in order to establish

the context for “What if” multiplication and

division problems. For example, the following is a

summary of The Three Little Pigs and an example of

a “What if” problem:

One day, the three little pigs decided to seek their

fortunes. They said good-bye to their mother and

then went on their way. The first little pig built

his house of straw, the second little pig built his

house of sticks, and the third little pig built his

house of bricks. The wolf huffed and puffed and

blew down the houses made of straw and sticks,

but he was not powerful enough to blow down

the house made of bricks.

After telling the tale, pose a “What if” problem similar to the following:

- What if the pigs’ mother gave each of her three sons five apples to eat on their journey?

How many apples would she need to take out of her fruit basket? (15 apples)

- What would you draw in your picture to solve this problem? (3 pigs with 5 apples each)

- What multiplication number sentence would match this problem? (3 × 5 = 15)

- What does each number in the number sentence mean? (3 pigs, 5 apples each, 15 apples in all)

- If you change the order of the numbers in the multiplication problem, will you get the same answer?

Show us. (yes; 3 × 5 = 5 × 3; Both equations make 15.)

- How could you change this problem to a division problem using the same numbers? (Possible

response: What if the pigs’ mother had 15 apples? How many apples would each pig get?)

- What division number sentence would match this problem? (15 ÷ 3 = 5)

- When you write a division number sentence, does it matter which number you write first? (Possible

response: Yes, in division you have to write the objects being shared first.)

- What does each number in the number sentence mean? (15 apples, 3 pigs, 5 apples each)

Present other “What if” problems related to the fairy

tale and ask questions similar to the ones in the previous

problem. Ask student pairs to draw a picture to

illustrate the action described in each problem and

write multiplication or division number sentences to

match each problem.

- What if the pigs’ mother needs to share 24 ice

cream bars equally with the 3 pigs? Does this

sound like a multiplication or division problem?

Why do you think so? (division; She is sharing or

dividing up a bunch of ice cream bars equally

among all the pigs.)

- What is a number sentence that describes the situation?

How many will each pig get?

(24 ÷ 3 = 8 bars)

- Could you also solve this problem with multiplication?

How? (Yes. I could think 3 times what number is 24. 3 × 8 = 24, so the pigs would each get

8 bars.)

- What if there were 4 little pigs and they each got

5 apples? Does this sound like a multiplication or

division problem? Why do you think so?

(multiplication; It is about 4 pigs each having

equal groups of apples and about the total number

of apples.)

- What is a number sentence that describes the situation? How many apples would the mother pig have given them? (4 × 5 = 20 apples)

- What if 4 pigs had to share 24 ice cream bars equally? Does this sound like a multiplication or division problem? (division)

- What is a number sentence that describes the situation? How many will each pig get?

(24 ÷ 4 = 6 ice cream bars)

- Show how to solve this thinking about multiplication. (4 × ? = 24; 6 ice cream bars)

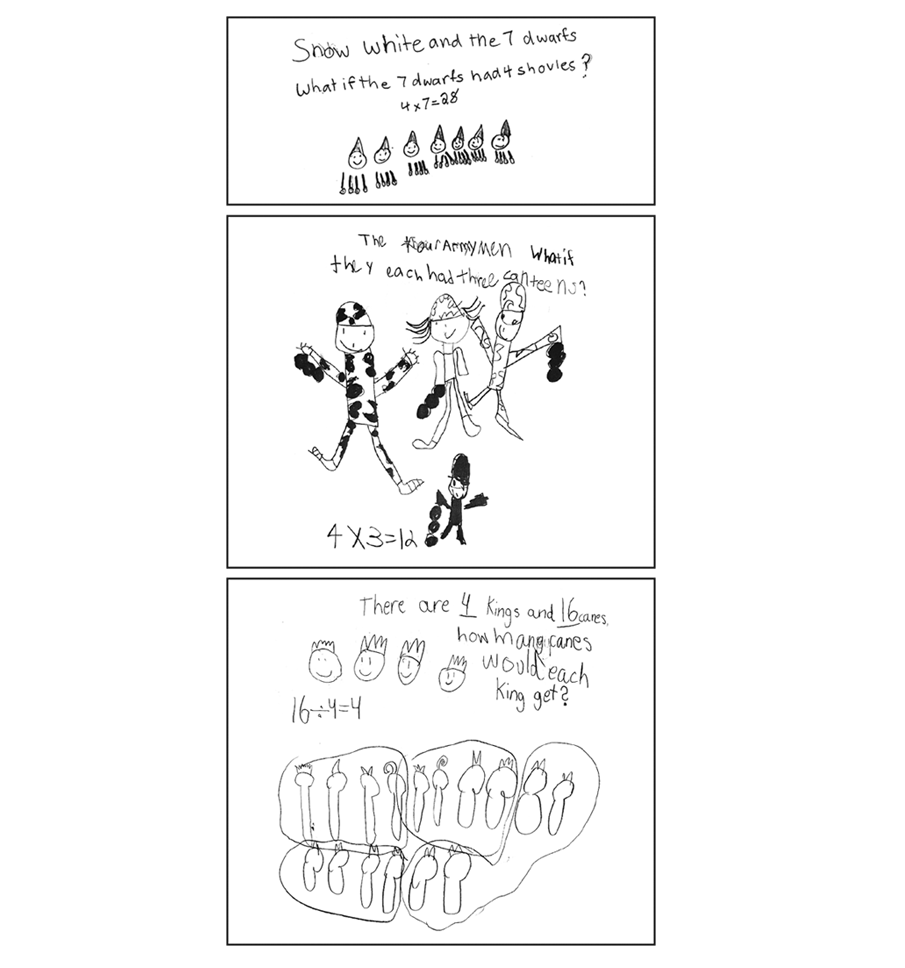

Write “What if” Problems. Reference other familiar tales with numbers in the story. Discuss “What if”

examples of multiplication or division situations related to these stories or other familiar stories. The following is a list of some examples:

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears: The three bears have

4 cereal bowls each.

- Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: The 7 dwarfs have

3 jackets each.

- Rumpelstiltskin: The queen guesses 5 names on each of the 3 days.

- Six Foolish Fishermen: 12 fishing poles are shared equally among 6 fishermen.

- Little Red Riding Hood: There are 3 wolves with 2 eyes each.

- Cinderella: 6 pairs of shoes are shared equally between the 2 stepsisters.

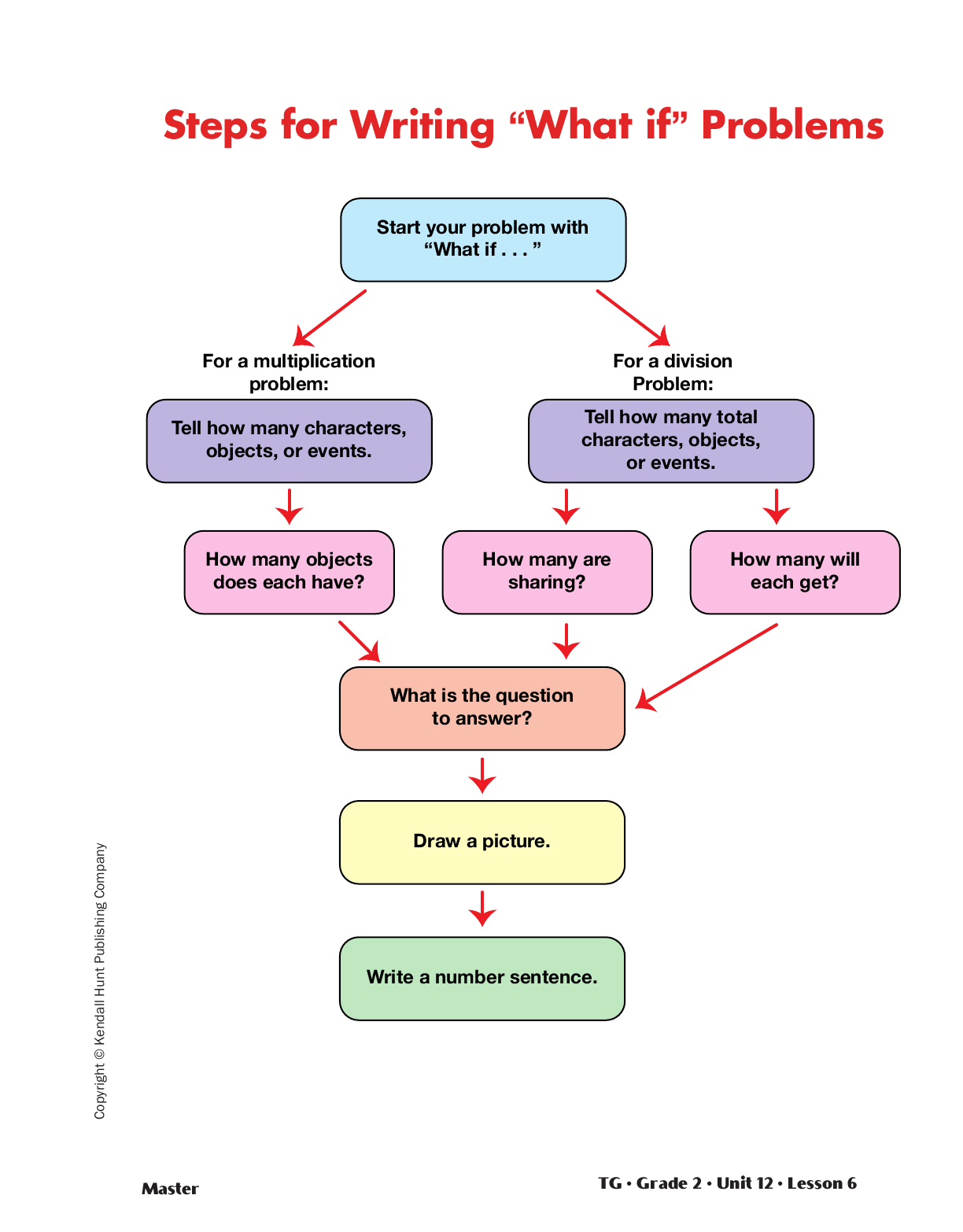

Display the Steps for Writing “What if” Problems

Master. Go through the flowchart of steps presented

on the Master. Distribute plain white paper or drawing

paper and have student pairs write a “What if”

multiplication problem and a “What if” division

problem. They can use situations from these stories

or they can create their own stories. See Figures 2

and 3 for examples. Connecting cubes or tiles should

be readily available for students who need to model

their problems with manipulatives.

Share and Solve “What if” Problems. Ask student

pairs to share their favorite problem with the class.

The other students should solve the problem. If the

problem is not written clearly enough for students to

solve, ask the class to suggest how to clarify the

problem. Thinking about problems and ways to

improve them increases students’ understanding of

the operation.