The Coat of Many Bits

Est. Class Sessions: 3Developing the Lesson

Use Square Centimeters to Measure Area. The Coat of Many Bits page in the Student Guide describes the context for the lesson. Ms. Alfonso's class is producing a play. Your students will assist with the production by helping to make the costumes.

The page explains that the front of the costumes will be covered with a fancy, colorful material. To do this, students first trace the outline of a coat onto a large sheet of paper. This gives them a picture (or model) of the coat. They use this model to find out how much material they need to cover the front.

In Unit 5 students measured area by tracing shapes on centimeter grids and counting square centimeters. In this activity, they count square centimeters using base-ten pieces. To do this, students need to know how many square centimeters each of the base-ten pieces covers. Help them discover this by having them lay the pieces on a copy of the Centimeter Grid Paper Master. Alternatively, you can use a display of the master to investigate this as a class.

Ask:

Give students time to discuss the questions in groups. Incorporate their suggestions into a discussion in which you model the activity by tracing the outline of a student's coat on the board or on a large sheet of paper (with the help of a couple of students).

Prepare to Measure Coats. There are several practical points to discuss, such as:

- Each group will find the area of only one coat; this will be the group's coat.

- The coats should be zipped, snapped, or buttoned and the sleeves should be extended.

- Hoods of coats should not be included since only the fronts of the coats will be covered with fancy material.

- The coats should be held flat against the surfaces they are traced on.

- Do not use markers when tracing because they may stain the coats.

Covering the entire outline with base-ten pieces is time-consuming. Encourage students to use their knowledge of symmetry to make the measuring go faster.

Ask:

Trace and Measure Coats. Distribute materials to student groups. We recommend that students trace the outlines of the base-ten pieces on the picture of their coat and figure out the area afterwards (Questions 1–2). This way, students have a permanent record of their work and can continue the activity if it is interrupted. Note that there will be some error in their measurements because the pieces will not perfectly cover the picture. This should be discussed at some point in the lesson.

Ask students to cut out their coat outline when they finish tracing the base-ten pieces. If students only find the area of half the coat, all written work can be done on the blank half. It can be done on the back if students cover the entire coat with base-ten pieces.

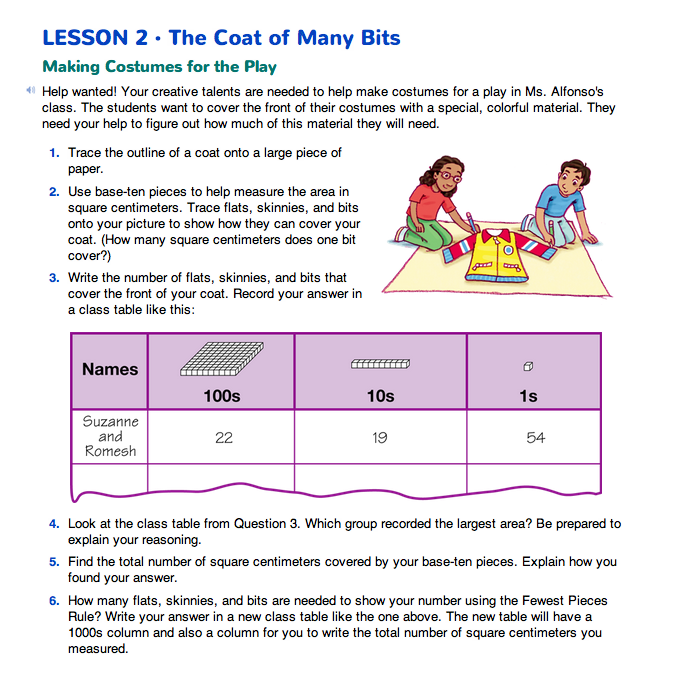

Record the Number of Base-Ten Pieces on the Class Table. Display the table you prepared for students to record their measurements as the number of flats, skinnies, and bits as shown in Question 3 and in Figure 2. In most cases, students will find that they have 10 or more each of the flats, skinnies, and bits. They do not need to change to the fewest pieces representation for this question. Remind them that they should report the pieces needed to cover the coat's whole front, not just the half they measured with base-ten pieces.

Question 4 asks students to find which group's number is largest. This will probably not be obvious since their numbers are not expressed using the fewest pieces. This should prompt a discussion of the advantage of writing numbers using the Fewest Pieces Rule.

Ask:

Find the Total Area. Question 5 asks students to find the total area of the front of their coat. This will take some time. Some might regroup their pieces using the Fewest Pieces Rule. Some might use baseten shorthand, and others might work with the actual base-ten pieces. Students will need packs to complete the trades.

Record Area on the Class Table. Display the second table you prepared for students to record the total coat area or their answers to Question 6 as shown in Figure 3.

Use the following discussion prompts to involve students in the creation of the table and in the decision of how many columns you should draw:

Students record their numbers on the table as described in Question 6, including recording the total number of square centimeters in the sixth column. The digits in their numbers in the area column should match those in the other columns of the table.

Question 7 asks students to compare the two tables. Here are some possible responses:

- They are alike because for each group, the same number of square centimeters is represented.

- They are different because:

- The numbers in the columns of the second table match the digits in the total square centimeters, but that's not true in the first table.

- The second table is easier to understand. I can compare the number of square centimeters more easily than in the first table.

- All of the numbers in the columns in the second table are less than 10. But in the first table there are many two-digit numbers.

Order Areas from Smallest to Largest. Question 8 asks students to arrange the areas of each coat in order from smallest to largest. Ask each group to record the area of their coat on an index card. On a bulletin board or chart paper, ask students to place their own index cards in the order that they think is appropriate. Discuss how students make their decisions, particularly if there are differences of opinion as to order. If students have difficulty with this, there is more practice provided later in the unit. Students can verify order of the areas with base-ten pieces or base-ten shorthand.

As students put numbers in order, ask:

Display the cutout coats in the order students arranged the areas. The coat sizes should appear to be in order from smallest to largest. Look for discrepancies in the order. Ask students for suggestions to explain the error and any big discrepancies between the areas of the different coats. Students may have measured the area incorrectly, they may have doubled incorrectly, or they may have ordered the areas incorrectly.

Compare Large Numbers. After completing the data collection and organization, students should complete Questions 9–12. In Question 9, the emphasis is on comparing numbers with benchmarks such as 500 or 1000 and not on computing exact solutions.

For Questions 10 and 11, encourage students to make estimates by thinking about the number of base-ten pieces (or the digits) in the appropriate places. For example, to answer Question 11, students must estimate the difference between their coat's area and 6000 square centimeters. They need only consider the largest places (base-ten pieces). They can think how many more 100s (flats) they need to make a 1000 and how many more 1000s (packs) they will need to have 6000 square centimeters.

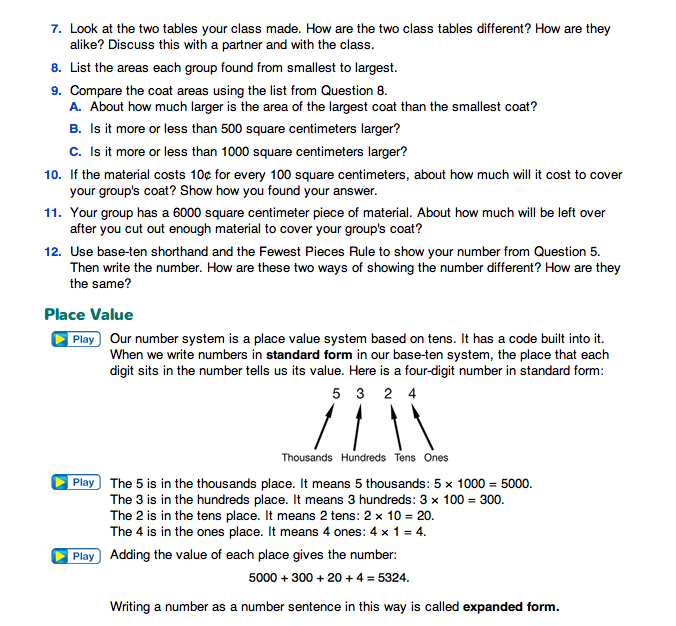

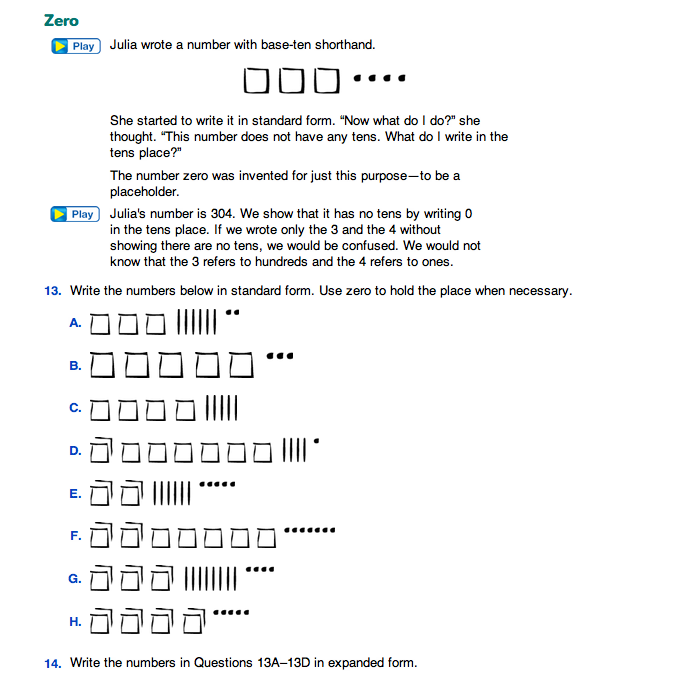

Examine Place Value. The Place Value section of the Student Guide formalizes the concepts that students explored in Unit 4. Read this section together as a class. It names the places as ones, tens, hundreds, and thousands, and introduces the terms standard form and expanded form. It also discusses the role of zero as a place holder. As students answer Questions 13–14, be sure they understand how to represent numbers that have zero in some of their places.

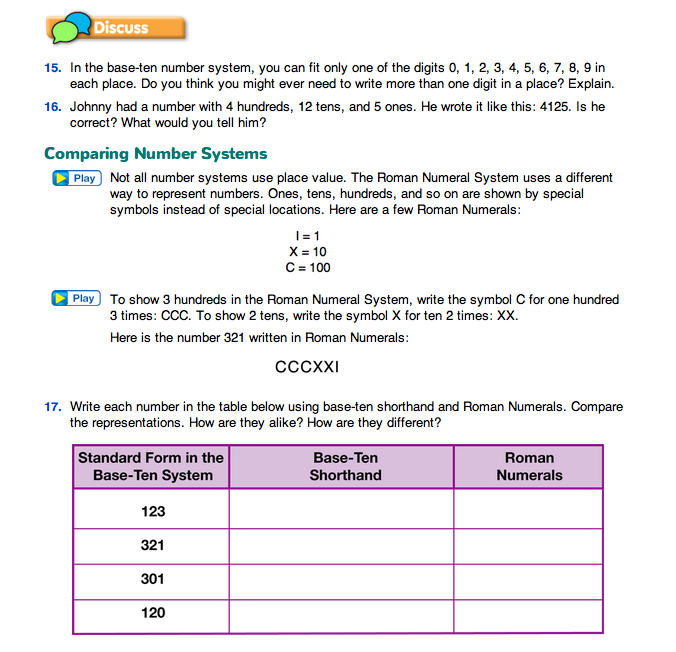

The idea of place value—that you write the number of ones, tens, hundreds, instead of repeatedly writing symbols to show all parts of a number—is important. But students might not realize that there are other number systems that do not use place value. The lesson introduces the Roman Numeral System briefly to give an example of such a system. It is not important that they learn the details of the system at this time, although some students might enjoy investigating it on their own.