Subtracting with Base-Ten Pieces

Est. Class Sessions: 2Developing the Lesson

Solve Problems with No Trades. As a warm up, ask students to solve a few problems that do not involve trading. Ask volunteers to show their solutions with a display set of base-ten pieces as the other students solve the problems with their own pieces. If you have enough pieces, it is best for each student to work with his or her own pieces.

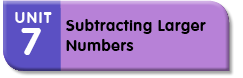

Begin with a problem such as 84 − 63 as shown in Figure 1.

Ask students to represent the number 84 with base-ten pieces. Then ask:

Ask students to work on other problems that do not involve trades, for example:

42 − 11 68 − 43

See the Sample Dialog 1 box for dialog taken from classroom video in which a student solves 68 − 43.

Solve Problems with One Trade. After solving a few problems that do not involve trading, students can begin exploring problems that involve trading.

For example, ask:

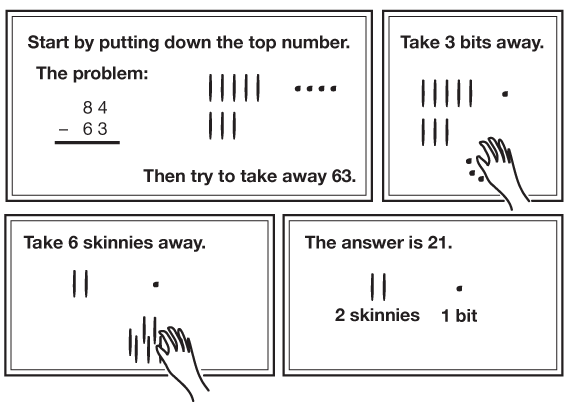

This problem is shown in Figure 2. As students work on the problem, circulate and see how they are dealing with the need to trade. If there are several students who do not know what to do, work together as a class to solve the problem. Otherwise, let students talk in their groups. Then ask students to show their work to the class using a display of base-ten pieces.

As students show their work, check their understanding of trading. Make sure they understand that trading does not change the number. It just changes the way it is partitioned. See the Sample Dialog 2 box.

Ask:

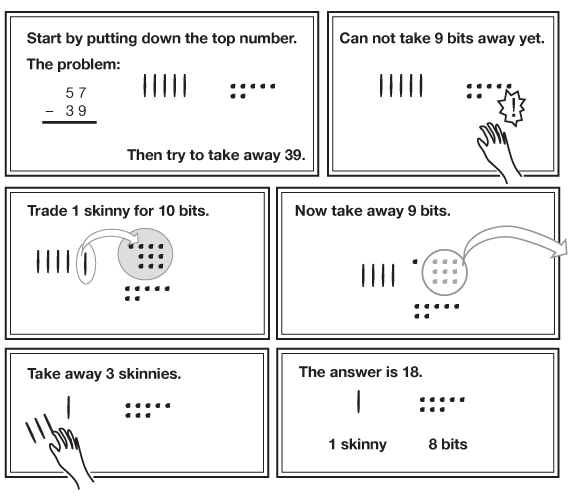

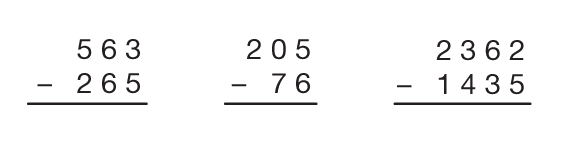

Provide several more problems that involve trading once, such as the problems in Figure 3.

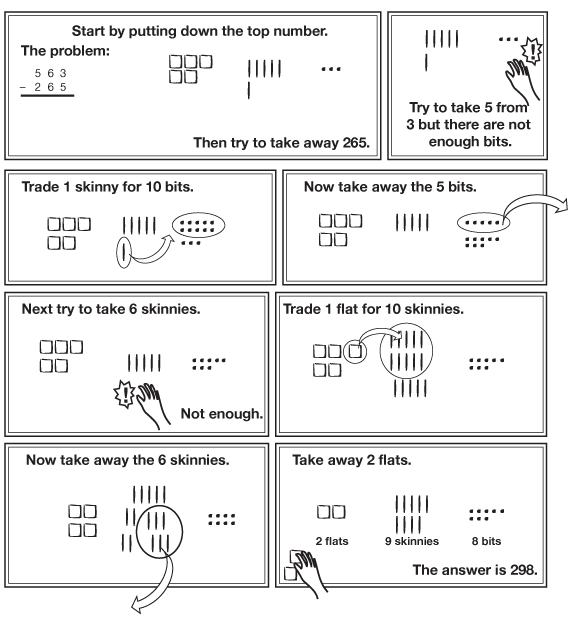

Solve Problems with Multiple Trades. Provide problems that involve trading more than once, such as the problems in Figure 4. Display the first problem 563 − 265 and ask students to use base-ten pieces to solve it independently. Again, make sure they are placing pieces to represent the number 563 only, and then removing the pieces that represent 265. Students may solve this problem in a variety of ways. Figure 5 shows one way to solve it, where students begin on the right by trying to subtract 5 ones from 3 ones, or take 5 bits from 3 bits. However, some students may begin the problem from the left instead. Others might find it easier to do all the trading first and then subtract. Discuss various approaches.

Ask:

Display 205 − 76. This problem involves a zero in the tens place.

As you work through the problem together, ask:

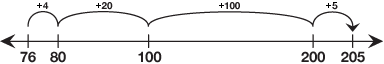

Encourage students to solve the problem a second way as a check. For example, they can use a number line and count up:

4 + 20 + 100 + 5 = 129

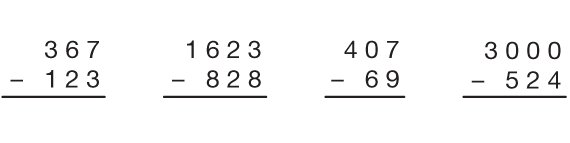

Figure 6 shows more subtraction problems that can be solved with the whole class together, in groups, or individually. The amount of guidance and practice needed will depend on students' experience. Do not expect mastery immediately. See Content Note.

Note that the last three problems in Figure 6 involve regrouping several times. Students often have trouble with problems such as the last one. Point out that the problems could be done by alternative methods that may be more efficient. Display 3000 − 524 and ask students to demonstrate some different solution strategies. For example, 3000 − 524 can be solved by first subtracting 2999 − 524 and then adding 1 to the answer. Using this method, no regrouping is required. 3000 − 524 can also be done mentally by first subtracting 500 (2500), then subtracting 20 (2480), and finally subtracting 4 to get 2476.

After students have shared a variety of solution strategies, ask: