Multiplication Patterns

Learning Fraction Concepts

Learning about fractions is more complex than learning about whole numbers… read more

Learning Fraction Concepts

Learning about fractions is more complex than learning about whole numbers. When students are beginning to learn about fractions, they need sufficient time to take part in experiences that allow them to develop an understanding of the quantities associated with fractions and the symbols that represent them. In this way, they will be less likely to apply whole number concepts inappropriately to fraction situations. For example, students may say that 1/4 is greater than 1/3 because 4 is greater than 3.

Fraction teaching and learning in Math Trailblazers is based on research in Math Trailblazers classrooms as well as the research of others. Students develop initial ideas through the use of multiple representations, including fraction circles, paper strips, number lines, and drawings. They make connections among these representations and to written symbols. Students use the models to develop concepts about the unit whole, equal parts of the whole, order, and equivalence before developing procedures for translating between symbols or computing with fractions. (National Research Council, 2001; Lamon, 2005; Cramer, Post, & delMas, 2002; Cramer & Wyberg, 2009)

What Are Fractions?

A fraction in everyday language is a part of a whole thing. We think of fractions as… read more

What Are Fractions?

A fraction in everyday language is a part of a whole thing. We think of fractions as numbers that look like 1/2 or 3/5 . Mathematically, a fraction is a number that can be written in this form ( a/b ) with certain conditions. The numerator and denominator must be whole numbers, and, since division by zero is problematic, the denominator cannot be zero. Using this definition 1/2 and 3/5 are clearly fractions. However, it is important to note that 5/5 and 5/4 are also fractions.

A source of confusion for students is that the symbols for fractions are complex and each fraction can be represented in multiple ways. Students most often see fractions as two numbers stacked on top of each other. They learn that the bottom number, the denominator, tells the number of parts the whole is divided into and that the top number, the numerator, tells the number of parts we are interested in. So, they think of the fraction as two separate numbers. However, as they become more sophisticated in their concept development, it is important for them to understand that 1/2 is a single number, just as 7 is. Furthermore, one-half can be represented in multiple ways such as 2/4 , 7/14 , 0.5, or 50%, but one quantity underlies all the representations.

Fractions are commonly written with either a slash (1/2) or “stacked” ( 1/2 ). Both ways are correct—although, at times, one or the other may be clearer.

Types of Fractions

Fractions can be interpreted in the following ways… read more

Types of Fractions

Fractions can be interpreted in the following ways:

- part-whole fractions

- the names of points on a number line

- indicated divisions

- pure numbers

- ratios

- probabilities

- measurements

A second source of confusion for students is that the same symbols are used for all of these kinds of fractions. For example, the symbol “ 1/2 ” can represent a part of an object (one-half of a pizza), a part of a collection (one-half of a class), a part of a unit of measurement (one-half inch), a ratio (one part milk to two parts flour), a probability (the chance of a fair coin showing heads), a pure number (the average of 0 and 1), and even a division (of 1 by 2).

“Instructional practices that tend toward premature abstraction and extensive symbolic manipulation lead students to have severe difficulty in representing rational numbers with standard written symbols and using the symbols appropriately.”

National Research Council, 2001, p. 234

Fractions Concepts

An example of a part-whole fraction is three-fourths in the statement,… read more

Fractions Concepts

An example of a part-whole fraction is three-fourths in the statement, “Last night I ate three-fourths of a carton of ice cream.” To understand what three-fourths means, it must be clear what the whole is: How big was the carton of ice cream?

It is also important for students to understand that the parts into which the whole is divided must be equal. The parts must have the same area, mass, or number. Many children think that any division into two parts is a division into halves; this is revealed by such statements as “I want the bigger half.” Many of the activities in this unit involve this notion of sharing (or dividing) into equal parts, or “fair shares.”

Sometimes, however, students carry this equality of parts idea too far. For example, when sharing money, it is not important that each person get the same number of bills and coins; all that matters is that everyone gets the same value of money. Similarly, if a rectangle is divided into fourths, the fourths may or may not have the same shape, but they must have the same area.

The whole in a part-whole fraction can be either a single thing (a pizza) or a collection (a class of students). When the whole is a single thing, the fairness of the shares depends on some measurable quantity (length, area, mass, etc.). Often, the area is the variable that must be equally allocated among the parts. Such a situation can be called an area model for fractions. When the whole is a collection, then counting is generally used to make fair shares. In this unit, there are wholes that are single things and wholes that are collections.

Fractions as Quantities

Other ideas in this unit include putting fractions in order by size and recognizing that… read more

Fractions as Quantities

Other ideas in this unit include putting fractions in order by size and recognizing that many names can refer to the same fraction (i.e., equivalent fractions). Specific procedures for solving such problems, however, are not included. Rather, students use their basic understanding of the meaning of fractions as quantities to work through the problems. When students have a firm grasp on fractions as quantities, then the learning of the procedures will be quicker and deeper.

Multiple Representations

Open number sentences make it much easier for students to think about the effects of… read more

Multiple Representations

Another important idea in this unit is multiple representations of fractions and making connections between those representations. Fractions can be represented in words, symbols, pictures, or real objects. It is especially important for students to be able to move freely among these representations.

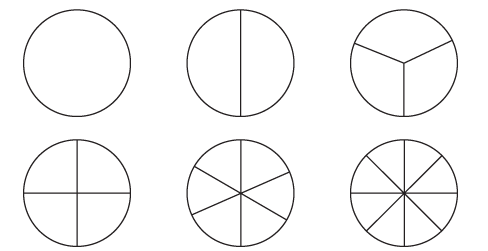

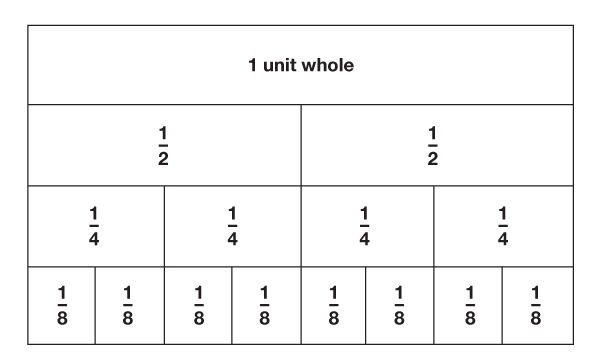

Based on the results of research in Math Trailblazers classrooms and the research of others, we have chosen to use circle pieces and the fraction chart model as area models in Grades 3–5. Research has shown that students use the circle model to construct mental images that support development of a variety of concepts and skills, including comparing fractions and estimating sums and differences. See Figure 1. Students build the fraction chart from folded paper strips as shown in Figure 2. The fraction chart model also supports the development of mental images that help students compare fractions. In particular, it develops students' understanding of the role of the denominator in determining fraction size (i.e., the larger the denominator, the smaller the fractional part) (Cramer, Post, and delMas, 2002; Cramer and Wyberg, 2009). For these reasons, students need sufficient time and opportunity to explore these models, so that they can use them as manipulatives and develop mental images to support their fraction learning in third grade as well as in later grades.

Figure 1: Fraction circle pieces

Figure 2: Fraction chart showing the relationship between halves, fourths, and eighths

MATH FACTS and MENTAL MATH

This unit continues the review and assessment of the multiplication facts to develop mental math… read more

This unit continues the review and assessment of the multiplication facts to develop mental math strategies and gain proficiency. Students will focus on the multiplication facts for the 2s and 3s.

Resources

- Cramer, K., M. Behr, T. Post, and R. Lesh. Rational Number Project: Initial Fraction Ideas, 2009

- Cramer, K., T. Post, and R. delMas. “Initial Fraction Learning by Fourth- and Fifth-Grade Students: A Comparison of the Effects of Using Commercial Curricula with the Effects of Using the Rational Number Project Curriculum.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 33 (2), pp. 111–144, March 2002

- Cramer, K., and T. Wyberg. “Efficacy of Different Concrete Models for Teaching the Part-Whole Construct for Fractions.” Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 11 (4), pp. 226–257, 2009.

- Curcio, F.R. (series editor). Understanding Rational Numbers and Proportions: Curriculum and Evaluation Standards for School Mathematics, Addenda Series 5–8. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Reston, VA, 1994.

- Lamon, S.J. “Fractions and Rational Numbers.” In Teaching Fractions and Ratios for Understanding Essential Content Knowledge and Instructional Strategies for Teachers. Routledge, New York, 2012.

- Mack, N.K. “Learning Fractions with Understanding: Building on Informal Knowledge.” In Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 21 (1), pp. 16–32, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. Reston, VA, January 1990.

- National Research Council. “Developing Proficiency with Other Numbers.” In Adding It Up: Helping Children Learn Mathematics. J. Kilpatrick, J. Swafford, and B. Findell, eds. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2001.

- Post, T., I. Wachsmuth, R. Lesh, and M. Behr. “Order and Equivalence of Rational Numbers: A Cognitive Analysis.” Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 16 (1), January 1985.

- Post, T.R., ed. Teaching Mathematics in Grades K–8, Research Based Methods. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 1992.

- Principles and Standards for School Mathematics. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Reston, VA, 2000.

- Wu, Hung-Hsi. “Part 2.” Understanding Numbers in Elementary School Mathematics. Amer. Math. Soc., 2011.