Multiples of Tens and Hundreds

Est. Class Sessions: 1–2Developing the Lesson

Use Base-Ten Pieces to Multiply. Direct students' attention to Question 1 on the Multiples of Tens and Hundreds page in the Student Guide. Reference the patterns for tens on the multiplication table and the notes on 10s from the Patterns for Remembering the Facts class chart when discussing the question.

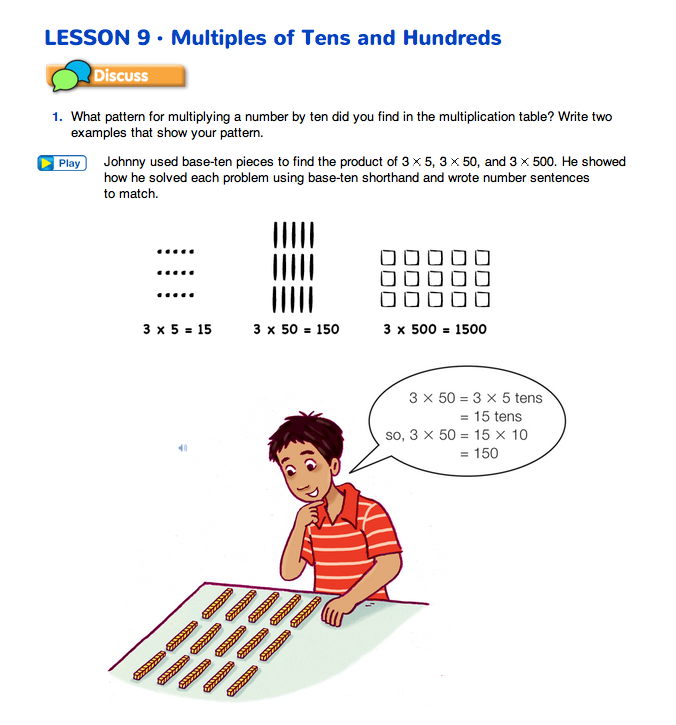

Read the short vignette that follows. It introduces the use of base-ten pieces to help students see patterns when multiplying numbers by multiples of ten or one hundred.

Ask:

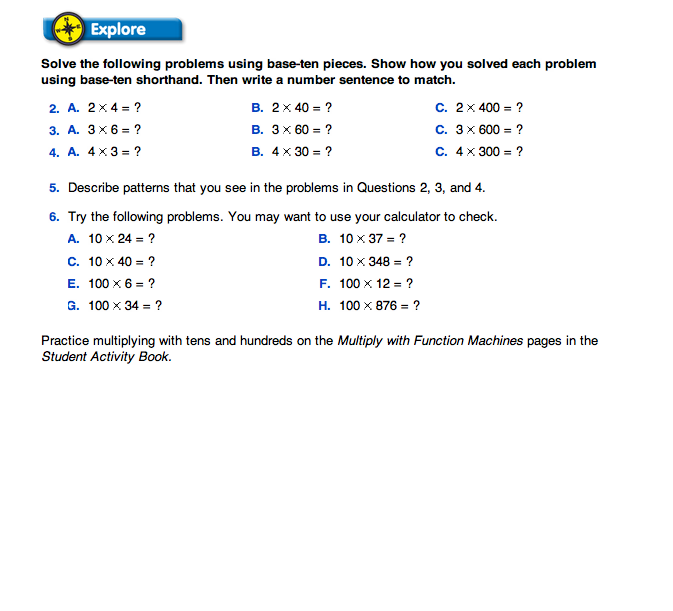

Assign Questions 2–6. Students will use base-ten shorthand to help them see patterns while solving problems and then describe the patterns. For Question 6, students use the patterns to make predictions about larger numbers and check their predictions with a calculator.

When students have finished, discuss Question 5.

Ask:

This pattern is correct and students may use it to solve problems. However, it is important to discuss why the pattern works. See the Sample Dialog in which the students are discussing 3 × 50 and 3 × 500. To remind students that they are multiplying by tens and hundreds, ask them to justify their answers for Question 4 with a display set of base-ten pieces.

Ask:

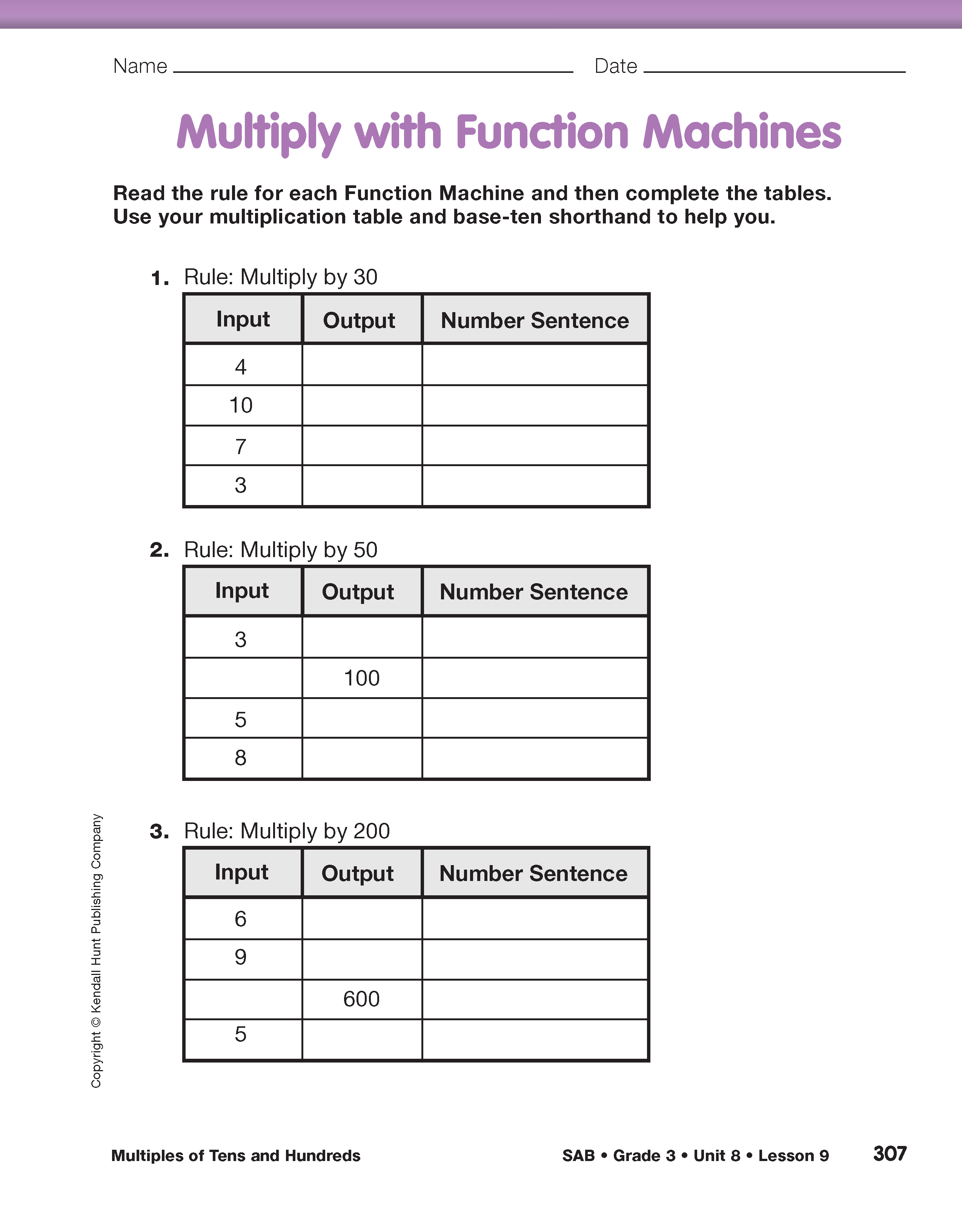

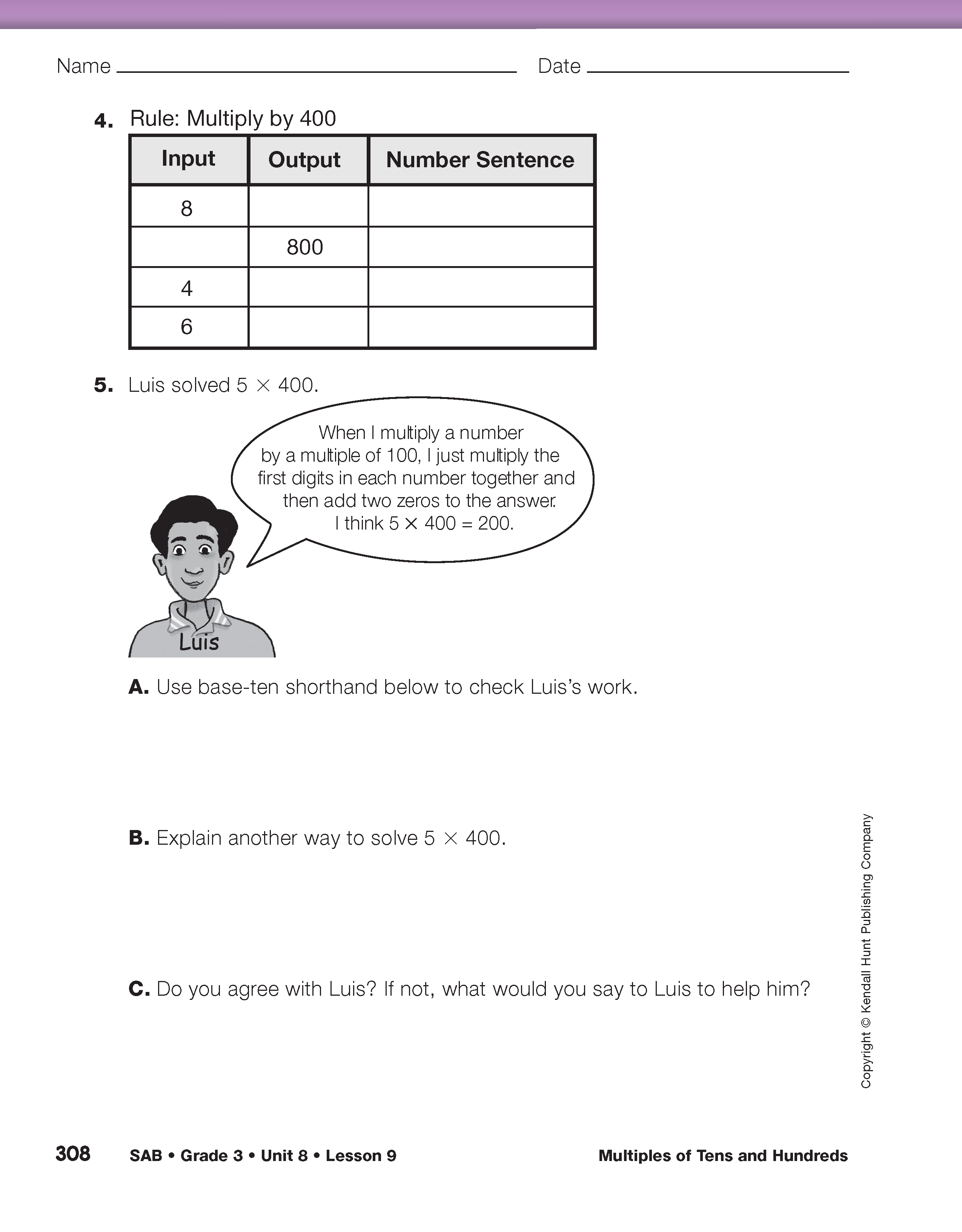

Multiply with Function Machines. Direct students' attention to the Multiply with Function Machines pages in the Student Activity Book. Assign Questions 1–5. Encourage students to use base-ten pieces or base-ten shorthand as needed to solve or check the problems.

When students are finished, discuss the problem 8 × 50 in Question 2. Some students may have difficulty when the fact within the problem itself generates a zero. 5 × 200 in Question 3, and 5 × 400 in Question 5 involve similar problems.

Ask: