Sandwich Mass

Est. Class Sessions: 2–3Before the Lesson

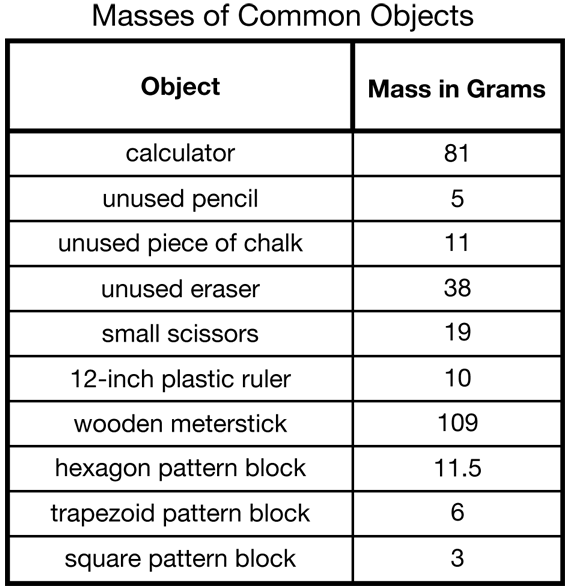

Review Measuring Mass. If students are not familiar with finding the mass of objects, they should complete the Mass Review Masters prior to the laboratory investigation. To assist students in becoming proficient in massing objects, set up stations throughout the classroom with objects for students to mass. Approximate masses of some objects found in one typical classroom are shown in Figure 1.

The Mass Review pages remind students how to zero their balances and compare masses with and without standard masses. Students find the mass of objects with a two-pan balance and record their mass in data tables (Question 1). Then they answer questions about the data they gathered.

The questions on the Mass Review pages refer to the possibility of measurement error. Students should realize reasons for measurement error include the limitations in the accuracy of the measurement instrument and skill of the experimenters. For example, the smallest mass in your set of standard masses will probably be one gram. So measurements can be accurate to only the nearest gram. Also, school kits of standard masses may not be precise.

Discuss the possibility of measurement error with your students. Encourage them to compare their data for the stations set up throughout the room.

Questions 2–3 ask students to identify the object with the least and the most mass. The answers to these questions will vary depending upon the objects students choose to mass. Students can either use their data tables to solve this problem, or they can compare the masses of the objects against one another using the two-pan balance.

Question 4 asks students to compare the object with the most mass to the object with the least mass. Students can compare the objects by saying that one object has about twice or three times the mass of the other, that one object has more mass than the other, or they may simply state the difference in the masses. Students can check the reliability of their data by placing each object on opposite sides of the two-pan balance and adding masses to the side with the least mass until the objects balance. Students can then compare the difference in their data tables to the difference on the balance. For example, if the masses of the wooden meterstick and the square pattern block in Figure 1 were compared, they would have a difference of 106 grams. In theory, adding 106 grams to the lighter side of the balance should balance the two pans. However, this may not happen due to experimental error. The difference of their masses on the balance could be 108 grams. Ask students to account for this discrepancy. The discrepancy may occur because a different wooden meterstick or square pattern block was used in the original data collection, the balance was not properly zeroed, because of rounding due to the limitations of the measurement tool, or inaccuracy of the standard masses.

Questions 5–7 explore the additive property of mass. Namely, the mass of two objects together is the sum of their individual masses. In practice, this may not work out exactly due to the possibility of experimental error. Students should base their predictions on the masses listed in their data tables and then check the reliability with a balance. Encourage students to discuss why any error may have occurred. Then ask students to come up with solutions for dealing with experimental error. Students may remember collecting data for multiple trials in previous labs. Lead them to the idea that measuring the mass of an object several times, then taking the mean or median mass, can help minimize experimental error. If students measure carefully, their predictions should not be off by more than 1 or 2 grams.